Tale of two cities

The Dawn: October 5, 2008

Tales of Two Cities sets out to tell that story — of independence, of upheaval and migration and of new beginnings — through the eyes of two observers, whose families were uprooted and who were forced to start new lives in new states in those unpropitious circumstances.

Tales of Two Cities sets out to tell that story — of independence, of upheaval and migration and of new beginnings — through the eyes of two observers, whose families were uprooted and who were forced to start new lives in new states in those unpropitious circumstances.

Kuldip Nayar, one of the India’s most eminent journalists, was 24 years old in 1947 when his father had to abandon his solid medical practice in the town of Sialkot and the family sought refuge with relatives in Delhi. They had initially decided to remain in Pakistan after Independence and were strengthened in their resolve by the assurances given to the minorities by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s first Governor-General. However, on Pakistan’s Independence Day, August 14, fear gripped the Hindu community in Sialkot so suddenly that the family got up from their lunch and left behind almost everything they owned. After a spell with friends in the neighbouring cantonment, they set off for Delhi, hoping to return once the situation normalised. But it was not to be.

Asif Noorani, distinguished Pakistani journalist and critic, was only five years old at Partition. He remembers the riots in Bombay and was aware of some horrific incidents in his neighbourhood. But the family weathered that storm and lived in Bombay for three more years before his father decided to migrate to Pakistan in search of work. His father’s business partner, the major shareholder in the medical store in which he worked, had already left for Pakistan and when his stake was taken over by a Hindu migrant from Sind, Asif’s father saw the writing on the wall. This was in fact a case of economic migration, undertaken with some reluctance, triggered by changing patterns of business ownership, and to a greater extent a matter of choice rather than compulsion.

As Asif himself writes: ‘Even those who were not in favour of Partition migrated to Pakistan in search of better opportunities’.

* * * * *

The Tales of Two Cities offered by Kuldip Nayar and Asif Noorani reflect very different Partition experiences. Kuldip’s migration from Sialkot to Delhi across the ethnically cleansed plains of Punjab was a very different experience from Asif Noorani’s family passage from Bombay to Karachi in 1950 on board the S.S. Sabarmati, a regular steamer service which continued to run until the 1965 war.

Their accounts of pre-Partition society and culture naturally reflect their age and circumstances at the time. Coming from what he calls ‘a secular-minded family of practising Muslims’, the young Asif Noorani seems to have been almost unconscious of other religious communities, assuming that Hindu school friends at his kindergarten must also be Muslims of some sort. Kuldip Nayar, on the other hand, had already graduated from the Law College at Lahore, had questioned Mr Jinnah in a public meeting and had heard Maulana Azad point out the potential pitfalls of Partition for the Muslim community. He was a politically conscious young man and had formed a peace committee with his friends in Sialkot to help to preserve good relations between the communities. — David Page

From Sialkot to Delhi

I did not want to leave Sialkot city. This was my home. I was born and brought up here. Why could not I, a Hindu, live in the Islamic state of Pakistan when there would be hundreds of thousands of Muslims residing in India? True, religion was the basis of Partition. But then both the Congress and the Muslim League, the main political parties, had opposed the exchange of population. People could stay wherever they were. Then why on August 14, 1947 was I unwelcome at a place where my forefathers and their forefathers had lived for decades?

Our family had other reasons to stay back. Most patients of my father, a medical practitioner, were Muslims. My best friend, Shafquat, with whom I had grown up, lived in Sialkot. At his mere wish I had tattooed on my right arm, the Islamic insignia — the crescent and star. I was a graduate in Persian. Pakistan had declared Urdu as its official language, with which I felt at home. We had a large property and a retinue of servants. Where would we go if we were to uproot ourselves?

Then our spiritual guardian was there. It was not a superstition but our faith that the grave in our back garden was that of a Pir who protected us and guided the family whenever it faced troubles. How could we leave the Pir? The grave was our refuge. We always found relief there. Our Ma, whenever harried or harassed or after her quarrels with our father, ran to the grave for solace. We, three brothers and one sister, bowed before the Pir every Thursday in reverence and lit an earthen lamp. It was our temple. The people of Sialkot were mild, austere and tolerant. They were cast in a different mould. Our religions or positions in life did not distance us from one another. We numbered about a lakh: 70 per cent Muslims and 30 per cent Hindus, Sikhs and Christians. As far as I could remember, we had never experienced tension, much less communal riots. Our festivals, Diwali, Holi or Eid, were jointly celebrated and most of us walked together in mourning during Moharram. Even our businesses depended on cooperative effort. There was a mixture of owners and workers from both communities.

Even at the height of the agitation over the demand for Pakistan, Sialkot did not experience any tension. Every day was like any other day and business was as usual. The Muslim League had probably taken out two or three processions for separation, like the ones the Congress party had for Independence. But there was no trouble. A few pebbles thrown into the water disturbed it for while. Otherwise, it was placid.

It was great to be alive. There was still daylight. As I looked out, relieved and happy, I saw people walking in the opposite direction. They were Muslims. I saw the same pain etched on their faces. They trudged along with their belongings bundled on their heads and their frightened children trailing behind. They too had left behind their home and hearth, friends and hopes. They too had been broken on the wrack of history. A caravan from our side was going to Pakistan. We stopped to make way for them. They too stopped. But no one spoke. We looked at one another with sympathy, not fear. A strange understanding cropped up between us. It was a spontaneous kinship, of hurt, loss and helplessness. Both were refugees.

There was a burst of happiness when Pakistan came into being. The Muslim population was on top of the world. The Sikhs were depressed. But most people took the whole thing in their stride. The atmosphere deteriorated only when Muslims ousted from India began pouring in and when it dawned on the Muslim population that they had an independent country of their own.

Yet there was no tension, not even a twinge of enmity. We spoke the same Punjabi. The Punjabi we spoke in Sialkot had a peculiar accent. I discovered this when I met Nawaz Sharif, then chief minister, for the first time at Delhi in the 1990s. It took him no time to tell me that I was from Sialkot. He said that the way in which I spoke Punjabi had a distinctive twang, a kind of accent, which was confined to the Sialkotees. I was in good company: the Subcontinent’s two great Urdu poets, Mohammed Iqbal and Faiz Ahmed Faiz, who were from Sialkot, spoke Punjabi in the same way. I had heard Iqbal one day at his mohalla, Imambara, where Shafquat had taken me. I was a child then and I never went near him out of fear. Even otherwise I would not have approached him at that time because he was speaking angrily in Punjabi. All that I remembered about him was his huge girth, sitting on a charpai (or string bed), which almost touched the ground because of his weight.

* * * * *

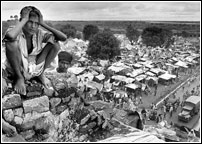

WE had killed one million of one another and uprooted 20 million. Temples, mosques and gurdwaras had been demolished in hundreds. The Subcontinent’s composite culture and pluralistic society going back hundreds of years lay in tatters.

It was late in the afternoon when the jeep reached the outskirts of Lahore. It halted there. We were told that a caravan of Muslims had been attacked at Amritsar and that the Muslims in Lahore were waiting on the roadside to take revenge. We got down and waited in fear and silence. There was some stray shooting in the distance. The stench of decomposed flesh from nearby fields hung in the air. We could hear people shouting slogans: Allah Ho Akbar, Ya Ali and Pakistan Zindabad. But it was far away. We set off again.

There was nervousness as we approached the border. And then we heard Bharat Mata Ki Jai. We drove past the hurriedly erected whitewashed drums and the Indian flag on a bamboo pole that marked the border. There was rejoicing and people on the Indian side hugged one another.

It was great to be alive. There was still daylight. As I looked out, relieved and happy, I saw people walking in the opposite direction. They were Muslims. I saw the same pain etched on their faces. They trudged along with their belongings bundled on their heads and their frightened children trailing behind. They too had left behind their home and hearth, friends and hopes. They too had been broken on the wrack of history. A caravan from our side was going to Pakistan. We stopped to make way for them. They too stopped. But no one spoke. We looked at one another with sympathy, not fear. A strange understanding cropped up between us. It was a spontaneous kinship, of hurt, loss and helplessness. Both were refugees.

The railway platform at Amritsar was so crowded that it was difficult to move without requesting someone to make way. People obliged quickly. Had the tragedy made them humane or had it taught them humility? It was so noisy that I had to shout at the top of my voice to make myself heard.

I did not know where they — hundreds of them — were going. Every train which arrived would be full in no time. I waited for the Frontier Mail to go to Delhi. I had to use all my force to get in. Squeezing in the bag required even greater strength.

I was taken for a Muslim in the 2nd Class compartment in which I rode. Non-Sikh Punjabis on both sides looked alike. They dressed in the same way. They ate the same food and even behaved in the same way. Everyone was condemning their leaders for letting them down. But I was abusing them at the top of my voice. I got attention, no doubt, but also some hostile looks.

My bare right arm flashed the crescent and star which I had got tattooed at Sialkot. I heard whispers of suspicion about my identity. Was he a Muslim abusing loudly to cover up his religion? The tattoo heightened the suspicion and convinced more and more people in the compartment that I was Muslim.

I was pulled out at Ludhiana, coincidentally the city where most people from Sialkot had migrated. Burly Sikhs with spears and swords joined a hostile crowd around me at the platform. I was asked to prove that I was a Hindu. I could see blood in their eyes. Before I could pull my pants down, a halwai (sweet-meat seller) from Sialkot, from our locality itself, came to my rescue. He shouted that I was Doctor Sahib’s son. Another joined him to confirm and the unbelieving people dispersed. This ended my agony as well as the excitement of the spectators. I was let off. But those few minutes still haunt me. There was no mercy those days. — Kuldip Nayar

From Bombay to Karachi

For someone born in 1942, Independence and Partition remain a somewhat hazy memory. However, I distinctly remember being taken by my father to see the illuminations on some buildings. We enjoyed the view from the upper storey of a double-decker bus in Bombay. That was perhaps on the eve of independence. I also recall the parade of the armed forces, a year later. The smartly turned out soldiers passed through Pydhonie, not too far from where we lived.

My pre-Independence memory is restricted to raising the then popular slogan ‘Up, up the national flag; down, down the Union Jack’ with other boys, after school hours, for many days. The only Jack I knew in those days was the one who went up the hill with Jill for that was my favourite nursery rhyme. I am sure most of the slogan-raisers from the missionary school, St Joseph’s High School at Umerkhadi in Bombay were, like me, unaware of the meaning of the slogan and even the significance of Independence. When someone asked me why I was chanting the slogan, I said because all my friends were doing it. I was at that time in what they called the Infant Class, the junior-most in the school.

I had earlier been to a kindergarten school called Dawoodbhoy Fazalbhoy School, which was run by the Ismailis (followers of the Aga Khan). It was a good enough school but I didn’t like it for two reasons. For one thing, they served only vegetarian food at lunch time and, for another, all the kids were made to take an afternoon nap. I was too restless to sleep at what were odd hours to me. I simply couldn’t close my eyes and was often punished for not letting my ‘neighbours’ — the kids lying beside me — go to sleep either. Eventually, a mattress was laid down for me in one corner of the room so that I could not disturb my classmates. My monthly reports said ‘good’ in all subjects and ‘very good’ in English but ‘bad’ in the column for conduct.

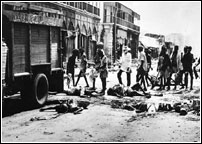

Though the school was in a predominantly Muslim locality, children from Hindu families were in significant numbers too. But when the communal riots began, some Hindu children moved to schools in what their parents thought were ‘safer’ environs.

St Joseph’s School, where my parents had both studied, was in what was considered a Hindu muhalla, but it had never seen any riots, at least not while we were in Bombay — until September 1950. Communal disturbances in those days were mostly confined to such areas as Dadar, Parel, Kalbadevi, Gol Pitha, Madanpura and Bhindi Bazaar.

My best friend in those days at St Joseph’s was a boy called Subhash Thorat. All I remember of him, apart from his name, is his crew cut and a question that I asked him: ‘Are you a Shia or a Sunni?’ He replied: ‘I don’t know. I’ll ask my father.’ I somehow thought that Hindus could be Shias or Sunnis too. I wasn’t sure who I was. I still wonder how the classification of the two main Islamic sects entered my mind, for ours was a secular-minded family of practising Muslims. Sects, castes and communal differences didn’t matter to my elders, which is something I inherited from them.

The same question was asked four or five years later in Lahore after we migrated to Pakistan but this time I was at the receiving end. A girl from my class, with whom I shared my sweets, posed the same question. ‘I guess I am a Sunni,’ I said. ‘Well, then I am a Shia. Remember! I can’t marry a Sunni boy,’ she responded with a grim face. I wasn’t particularly interested in marrying her, at least not at the age of ten, but I did lament the loss of an option.

* * * * *

One incident, which is deeply etched on my memory, is the news of the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. My parents were particularly worried about the safety of my uncle, Malik Noorani, and his wife, Mumtaz Noorani, both hardened leftists, who had gone to Delhi to attend the wedding of poet Ali Sardar Jafri and Sultana at that time. Everyone feared that the assassin was a Muslim, so the marriage party was disrupted and all those present, including the newlyweds, fearing the outbreak of a communal riot, rushed to safer places. When it was confirmed that the assassin was a Hindu, policemen in trucks announced on their megaphones: ‘Gandhiji ka qatal kisi Musulman ne naheen balke eik Hindu ne kiya hai.’ (Gandhiji was not assassinated by a Muslim, but by a Hindu). Thus, what could have led to as bloody a riot as the anti-Sikh riot in Delhi in 1984, after the two Sikh bodyguards of Indira Gandhi opened fire at her, was averted by the presence of mind shown by the authorities.

One incident, which is deeply etched on my memory, is the news of the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. My parents were particularly worried about the safety of my uncle, Malik Noorani, and his wife, Mumtaz Noorani, both hardened leftists, who had gone to Delhi to attend the wedding of poet Ali Sardar Jafri and Sultana at that time. Everyone feared that the assassin was a Muslim, so the marriage party was disrupted and all those present, including the newlyweds, fearing the outbreak of a communal riot, rushed to safer places. When it was confirmed that the assassin was a Hindu, policemen in trucks announced on their megaphones: ‘Gandhiji ka qatal kisi Musulman ne naheen balke eik Hindu ne kiya hai.’ (Gandhiji was not assassinated by a Muslim, but by a Hindu). Thus, what could have led to as bloody a riot as the anti-Sikh riot in Delhi in 1984, after the two Sikh bodyguards of Indira Gandhi opened fire at her, was averted by the presence of mind shown by the authorities.

I remember clearly that one morning my father, who used to go out every day to pick up freshly baked bread and the day’s copy of The Times of India, entered the house with a sullen face. He announced the death of Quaid-e-Azam, Muhammed Ali Jinnah. My knowledge of Mr Jinnah was confined to the slogans which some people in the neighbourhood used to raise: ’Quaid-e-Azam zindabad, Pakistan paindabad’. But after Partition the slogans died down — discretion being the better part of valour.

* * * * *

When I compare Mumbai and Karachi, I sometimes feel they are twins that were separated at birth. The white collar workers and the labour class in both countries make a beeline for these two great cities. It’s a Gold Rush kind of a situation. The weather in both the cities is moderate, except that Karachi doesn’t get even half as much rain as Mumbai, and both suffer from increasing congestion and pressure on services. Every time I go to Mumbai I find it more claustrophobic. The traffic, though more disciplined than in Karachi, drives me crazy particularly during the rush hour. When I visited the city in 2007, it took me an hour and a half to reach South Mumbai from the airport with the result that I could not visit friends and relatives living in places like Bandra and Juhu, not to speak of more far flung suburbs during my short stay.

Mumbai scores a major point over Karachi in its control of crime. There are occasional gunfights between Mafia groups in Mumbai but otherwise it is city free from major crimes. Robberies are much less in number and cars are not snatched at gunpoint. The one plus-point that Karachi has is that you don’t find people walking without shoes, nor do you see people sleeping on pavements. People sleeping on pavements in Mumbai are a sore sight.

Karachi and Mumbai have both been plagued by bomb blasts, but megacities as they are, the unaffected areas continue to function more or less normally. Besides, they are both highly resilient. All said and done, there is no city in the world I love to visit more than Mumbai but if I am asked to choose between Mumbai and Karachi my vote will go to Karachi. In fact, after more than fifty years as a resident, I have come to feel about Karachi in much the same way as Milton wrote about England — ‘With all thy faults, I love thee still.’— Asif Noorani

Excerpted with permission from

Tales of Two Cities

By Kuldip Nayar and Asif Noorani

Roli Books, New Delhi Available at

Liberty Books, Karachi

126pp. Rs545