Bhangra spreads its empire

[Courtesy: Observer Music Monthly. London. October 14, 2007]

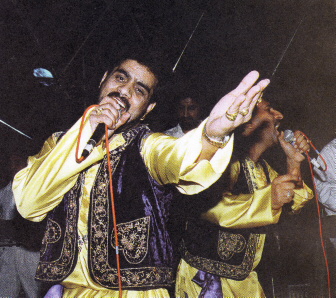

Malkit Singh. 1996

The west London Mela which takes place every August is the British-Asian Glastonbury and the perfect place to catch up with the heroes of homegrown bhangra, the top singers from the sub-continent, and new faces on the UK-Asian dance music scene: Panjabi MC, the Panjabi Hit Squad, Jazzy B and the rest of the clan. Between the funfair, curry and samosa stalls, sari kiosks and kofi ice-cream sellers, are several stages and music tents. Family groups picnic on the grass while their unwed offspring throng the stages to dance, pose and flirt.

At the London Flavas stage, where the Sony-award-winning BBC Radio 1 DJ, Bobby Friction, and his DJ partner, Nihal, are geeing up the crowd as if working a wedding party, I'm locked in with a group of 19- and 20-somethings from Southall and east London. The parents are 'over there'. When Birmingham's superstar bhangra singer, Sukshinder Shinda, now in his mid-forties, fills the air with the sharp, thunderous rhythms from two dhol drums (the instrument synonymous with bhangra) and his cinematically heroic voice, the cheers are deafening. When he bursts into 'Par Linghade', an old Punjabi folk tune given the bhangra treatment, the girls squeal. Nineteen-year-old Sheena from Chiswick, whispers: 'This has been around for years - it's the Indian version of the Romeo and Juliet story, and we all love it.' Their male friends, in turbans and baseball hats, fling up their arms and sway like dazed cobras, and everyone sings along.

This cross-generational response to bhangra has helped keep it moving and developing for almost three decades - but surely, I suggest, this is their parents' music? 'Oh, no,' the high street trendy girls and the girls in chic hijabs, insist, 'we still love the old songs, even though bhangra's got more modernised with the remixes and rapping.' Sheena's friend, Manjit, interrupts, 'It's not just for our parents' generation,' and Kuldeep, 22, in hip hop stripes, adds, 'Everything that's coming up now is old-school songs remixed.' They've already seen British bhangra pioneers, Southall-based Heera, with their paunches and mature voices and still compelling hits, and Kuldeep says: 'Our parents love Heera's old songs and so do we - particularly the remixes.'

When I tell Bobby Friction this after one of his nightly BBC Asian Network shows, he's happy to hear that the music is being enjoyed down the generations, but sad because he thinks the young musicians are lazy. 'They're just playing the old songs, not writing their own.' None the less, he concedes: 'The first track on every one of my shows for the Asian Network has to be bhangra; that ticks every box for the whole international audience.'

From humble beginnings as the music of poor Punjabi farmers to the Eighties 'Golden Age' and British bands such as Alaap and Heera to today's fusions with hip hop and grime, bhangra has travelled far over the past 30 years. Cast back to the wedding party in Bend it Like Beckham when the heroine, Jess Bhamra, tries desperately to slip out of her sari and into football shorts, while the grannies from No.42 and hunky men in turbans wave their arms in the air and cheer to the rhythms of drummers in gaudy robes and matching turbans: that's bhangra. And at Live8, 2006, when UB40 played with the thunderous drumming of the Dhol Blasters - sinuous female dancers and men in glittering turbans with fan-shaped coxcombs, directed by the leading UK bhangra drummer, Gurcharan Mall: that's bhangra. The original bhangramuffin, Handsworth's Apache Indian, made his career following the Jamaican line, but still has bhangra flowing through his blood and helped put it in the UK charts and on the international map in the early Nineties.

Heera on stage. 1987

Bhangra is part of every Punjabi Briton's life, regardless of whether they arrived in the 1960s wave which established the UK's largest community, in Birmingham, or in drifts from post-Amin Uganda, or – like Bobby Friction and most bhangra artists - were British born. 'I didn't have a militantly Punjabi upbringing with an exclusively bhangra soundtrack,' says Friction. 'We had Bollywood at home too. The people I grew up with in Hounslow were also into soul and funk and I was into Madness and Prince, as well as Alaap and Heera's new style Punjabi songs. And our parents listened to the originals of those songs on records at home.'

For the Sikh families lured to Britain in the Sixties by jobs in London or in Birmingham's fading steel industry, the traditional songs and dances were a vital consolation. These former farmers came from lush agricultural valleys in the north west, the breadbasket of India, and their music and dances related to the crop seasons and celebrations centred on the annual harvest festival, Vaisakhi (13 April, still a crucial date on the now urban community's calendar).

Bhangra was traditionally a men's dance, accompanied by rousing rhythms created by the double-headed barrel-drums, the dhol, beaten at each end with a stick. The UB40 dholi Gurcharan Mall arrived in Birmingham in 1963, and was in at the birth of the UK scene. Sitting in his front-room in Handsworth, surrounded by cabinets crammed with trophies, Gurcharan tells a story typical of his generation. He served an apprenticeship in mechanical engineering but, he says: 'I was always banging on the machines and getting on people's nerves! So I got together with workmates to practise; there were no teachers then and no drums, everything was imported; we had to bring in the goat skins [for drum-heads] from India, wrapped in blankets!' Nowadays, he makes beautiful drums in the garden shed.

Gurcharan's performance at Live8 reinforced the presence of bhangra on the British music landscape. Ammo Talwar, director of Punch records in Birmingham, recalls the reaction of friends: 'It was very emotional: the only Asian person on Live8. Then, typically, no ligging backstage with McCartney or Geldof or Madonna; he drove straight to Birmingham for a gig!'

During a mini-tour of Birmingham's bhangra landmarks, Talwar drives along the arterial Soho Road, the Midlands' equivalent of Brick Lane. It cuts through the Sikh community, past the magnificent temple, into the bhangra-zone, and adjacent reggae-lands of Handsworth; crossover musicians such as UB40 and Apache Indian were inevitable given such proximity. The road was uniquely Punjabi for decades and while it is now also home to Kurdish and Eastern European arrivals, the sari shops, sweet shops, cafes and music stores are strictly Asian. The latter, packed with homegrown and imported CDs and videos, reveal the popularity of bhangra on home turf. The area still houses many musicians and studios, which attract performers from India and the US. Shopkeeper Ravi Singh says: 'If you go to India and say Soho Road, they still know our music today.'

Sat Kapoor of Jalandhri origin known as Apache Indian

In a cafe off Soho Road, we meet Gursharan Chana, aka Boy Chana, a neatly dressed Sikh with a penchant for black turbans and suits. A leading bhangra DJ and former music journalist for the Asian weekly Eastern Eye, Chana's photographic archives form a key part of a current touring exhibition, 'From Soho Road to the Punjab', and accompanying book, Bhangra: Birmingham and Beyond, by Dr Rajinder Dudrah of the University of Manchester. The boxes labelled 'Daytimers' contain a social history of the UK bhangra scene, while another holds images from the 1985 Handsworth riots which helped launch Gursharan's career as a photographer after journalists used his family home as a base to cover the trouble.

In the Eighties, Punjabi folk music transformed into a British-based original, with its stars being Alaap and Heera, both from Southall in west London, who added drum kits and synthesisers. Dance with Alaap (1981) stands as one of the key records in British bhangra. Both bands became so popular that fans would gatecrash weddings at which they were playing. Crucially, a live scene began to develop, with Birmingham's Oriental Star emerging as both a label and a promoter of bhangra gigs. Gurcharan Mall remembers that the music spread after the Asian cinemas were killed off by imported home videos from India, when canny entrepreneurs re-opened the same venues during the daytime for gigs and, in one swoop, transformed the social life of young Asians and launched the bhangra boom.

Bobby Friction's memories of those heady days are typical: 'I turned 15 in 1986,' he says, 'and I'd go from school to the first Daytimers, at the Empire, Leicester Square, in the afternoons. The girls went into McDonalds' toilets to change and put on their make-up. There was nothing outside our front doors then for young Punjabis and British Asians; it was like being Azerbaijani in London today. We had a chance to go to a nightclub in the West End during the daytime - white and black kids couldn't do that!'

I stumbled into a Daytimer at the Astoria on Charing Cross Road in London in the late Eighties and bumped straight into a grinning Andy Kershaw, who - with John Peel - was the first non-Asian DJ to play bhangra on BBC radio. Two thousand cheering and dancing young Asian kids, dressed to the nines in the sweaty heat, in turbans and shalwar kameez, 501 jeans and flares, were entranced by thunderous dhol beats and disco-inspired keyboard melodies. The singer's high, hard (macho) voices were backed by repetitive choruses and the ecstatic drums. I might have seen Alaap or Heera, but sadly, the details are locked in a faint Travolta-ish memory. I regret having missed the all-girl trio Saffron, who included Meera Syal (their Farrah Fawcett hairdos and bright outfits didn't save them from their doomed music), and the young tabla player Talvin Singh, sporting a bouffant hair-do in a photograph of Alaap from 1987.

The singer known as Shin, who still leads the Eighties band DCS, remembers girls leaving home in school uniform and transforming themselves at the clubs. 'Their mums and dads never knew,' he says, now revealing fatherly concern. 'And eventually, there was a lot of hoo-hah because members of religious organisations approached the bands who they said were 'corrupting' the kids. It was very innocent when it started but after a couple of years, when the alcohol and then the drugs came in, we took a back step.'

Ammo Talwar sees the social significance of those sessions: 'Asian girls couldn't go out at night, for cultural reasons, but we created the little spaces in the daytime. It was a meeting-ground, almost like a secret underground at a time when there was a lot of racism. The notion of sharing with your white European counterparts didn't exist until the early Nineties. It became very similar to rave culture, with sponsorship involved, money to be made, kids bunking off. But from that, a new generation was liberated.'

In the Eighties, DCS followed in the wake of Heera and Alaap, taking the music forward by incorporating influences from the Beatles and Led Zeppelin to what singer Shin calls 'the big synth sound of Duran Duran and the Thompson Twins'. Shin describes their style: 'The drum is massive and loud, and the tumbi [the traditional one-stringed instrument with a twangy guitar-like sound] works with the dhol to produce the basic bhangra sound and rhythm - which must be in 4/4 which came from disco; we started out when disco was massive in Asian films.' Their 1991 12-inch, 'Rule Britannia', a call for national unity in the face of building racism, is remembered especially for its cover: a witty spoof of the Lord Kitchener First World War call-up poster, his stern face now framed by a Union Jack turban and the Indian tricolor.

The sharp, repetitive little melodies of the tumbi insinuated themselves inside the infectious, early remixes by Birmingham's visionary producer, Bally Sagoo. The Quincy Jones of British-Asian music, Sagoo once described his recipe to Time magazine: 'A bit of tablas and a bit of the Indian sound, but ring on the bass lines, the funky drum (dhol) beat and the James Brown samples.' His 1991 compilation Star Crazy helped shoot bhangra around the world, and includes a remix of the Pakistani qawwali (Sufi songs) virtuoso singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, whose sublime voice fits effortlessly into the bhangra rhythms, Hollywood strings and Latin vibes. Sagoo's 'Dil Cheez' ('My Heart') reached number 12 in the UK charts in 1996, and its success took him to Mumbai to open for Michael Jackson.

Star Crazy also includes 'the Golden Voice of the Punjab', Indian-trained Malkit Singh, who still performs in the traditional narrative boliyan style, and whose Eighties hits have become remixers' favourites. Sagoo's compilations pointedly included some of the rare female bhangra singers: Rama Mohinder Kaur Bhamra, and Sangeeta.

Meanwhile, Apache Indian - Steven Kapoor - followed his Afro-Caribbean school friends into reggae. 'Steel Pulse were very inspirational,' he says, lounging in the bar of Handsworth's Drum community centre. In a rasta-striped tracksuit, his locks tied up in a bundle, he explains his approach to recording. 'When I first went into the studio,' he says in a surprisingly soft, un-Jamaican accent, 'I didn't want it to be just reggae, so we put a bit of the Punjabi rhythm in there - the first time bhangra was being fused musically, just like our lifestyles.' Today, Apache, 40, is an international ambassador for bhangra, but the years spent on the reggae circuit have cost him some success at home, especially among young British Asians. Shin recalls Apache's early mixes as 'very desi [Punjabi] and ragga' but as his star waned, Panjabi MC stepped up to take his place and set bhangra beats on a course towards the mainstream with his hit 'Mundian To Bach Ke' (Beware of the Boys) - which was later remixed by Jay-Z.

Apache's 2005 album, Time for Change (Revolver), marked his return to the fold with the dhol drummer Bubzy. It features a gorgeous bhangra-ragga-ska re-make of 'Israelites' with Desmond Dekker, and contributions from the young US-based female bhangra singer Gunjan (a Bally Sagoo discovery), who adds her gorgeously sugar-and-lime vocal textures to 'Prayer for Change'.

Soho Road is now home to another generation of controversial artists. Hard Kaur is not strictly bhangra but she has never escaped its influence. Living above her beauty salon (speciality, Asian brides' make-up), the 28-year-old's image varies between spiky punk and Bollywood heroine while her sharp, deep voice, heard on new album Supawoman (Saregama Rec), is harnessed to her preferred medium of hip hop and rap. Hard Kaur's lyrics are part of the appeal - and a source of friction: a tough, independent woman, she criticises British racism, relishes the power to play with her culture's sexual rules and roles, and encourages women to make their own choices.

Parallel stories of bhangra existed in Birmingham and London, as Bobby Friction notes: 'The Eighties London sound was a bit more innovative, open to Hindi and other Asian music, whereas Birmingham was desi because the community was solid, Punjabi and Sikh. It had an authentic rawness whereas London's was more poppy popular. Today, a lot more kids in London are sampling grime and hip hop and doing remixes of bhangra classics than in the Midlands.'

Bhangra's influence is reaching ever wider. The XBox hit 'Project Gotham Racing 3' is the first computer game with a bhangra soundtrack; the 2012 Olympics arts supremo, Jude Kelly, is rumoured to be planning a mammoth 350-strong dhol drum marathon at the opening ceremony; bhangra beats, courtesy of the UK's Rishi Rich Project, have been hitched to R&B tracks by Missy Elliott, Britney Spears and Craig David.

Bobby Friction's tastes roam the spectrum and fly into the future. He raves about Word is Born and Reprazent by Specialist N Tru-Skool from Coventry and Derby: 'Straight up hip-hop bhangra albums with hard grime influences. And still Punjabi.' He adds to the list Tru-Skool's new solo album, Raw as Folk - 'the most desi, most Asian, most sub-continent, most Punjabi album: brilliant.'

Rhythm Dhol

Friction says 90 per cent of his playlist is 'bedroom stuff' sent directly to him as MP3s that have been made on laptops at the artist's or producer's home. 'Sharma Ji from New York sends me remixes of UK bhangra with house woven in, and plays dhol drum.' On the other hand, DJ Swami's new album is 'without a single traditional bhangra track on it - one track absolutely filthy house, another sweet R&B funk, New York-style. But all in Punjabi!' he roars.

Ammo Talwar says: 'There will always be many sub-genres around Bhangra and it's always metamorphosing into new genres, but while musical trends come and go, bhangra is really here to stay.' Then he shouts out the bhangra catch phrase, which says it all: 'Chak de Pattey! (tear up the floorboards!) - Rock the House!'

Best of bhangra: Bobby Friction's choices

1. DJ Sanj, 'Das Ja' (Envy Records)

This is a rip-roaring 21st-century bhangra anthem. Folk music in sound, but produced and mixed down with electronic sensibilities.

2. Panjabi MC, 'Mundian To Bach Ke' (Nachural Records)

The Big Daddy crossover that everyone knows. Simply stunning in its ability to wreck dancefloors.

3. Gurdas Mann, 'Apna Punjab Hove' (Moviebox)

Bhangra's poet in residence and folk hero sings his own song that is now the unofficial Punjabi national anthem.

4. Heera, 'Holle Holle' (Arishma)

A landmark track that took British bhangra by the scruff of its neck in the late Eighties and showered it with synths and dance beats. The first bhangra 'house' track.

5. Alaap, 'Bhabiye Ni Bhabiye' (Multitone)

Veteran Brit-Bhangra band led by the charismatic Channi Singh. The soundtrack to my youth and a million and one weddings in small town halls across the UK.

· Bobby Friction and Nihal's Radio 1 show, midnight-2am on Tuesdays. The exhibition 'From Soho Road to the Punjab' is at ExploreMusic at the Sage Centre, Gateshead, throughout October, and then touring the UK. 'Bhangra: Birmingham and Beyond', is published by Birmingham City Council. For more information, visit

www.sohoroadtothepunjab.org