Harjap Singh Aujla

MOHAMMAD RAFI’S EARLY YEARS IN AN UNKNOWN VILLAGE IN RURAL AMRITSAR

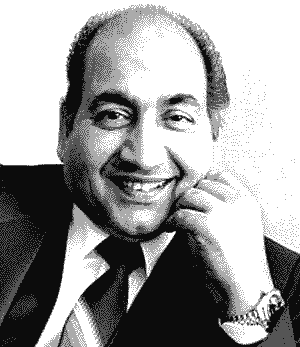

Punjab must be genuinely proud of its great son Mohammad Rafi, who was born in a non-descript hamlet in a remote rural area of Amritsar district. Starting from a humble and modest beginning, he rose to become the most prolific film playback singer of the movie industry, not only in India , but in the whole world.

Punjab must be genuinely proud of its great son Mohammad Rafi, who was born in a non-descript hamlet in a remote rural area of Amritsar district. Starting from a humble and modest beginning, he rose to become the most prolific film playback singer of the movie industry, not only in India , but in the whole world.

The Punjabis should be doubly proud that two of their sons have ruled over film singing for more than half a century. K.L. Saigal was the first Punjabi singing star, who dominated the Indian film industry for a decade and a half from 1933 to 1947. The Indian film industry switched over from silent movies to talkies in 1931, when film “Alam Ara†was made. But ever since actor singer Kundan Lal Saigal started his film career in the eastern metropolis of Calcutta in 1933, he did not look back and went from strength to strength, until death put a sudden end to his brilliant career as a singing leading actor in the dark year of 1947.

When Saigal’s health was deteriorating, Mohammad Rafi was warming up to step into Saigal’s spikes. Mohammad Rafi’s success story is indeed a story of rags to riches. He was born in a village called “Kotla Sultan Singh†near the town of Majitha in the then Punjab ’s second largest district of Amritsar. Most of the land in his village was owned by Sikh farmers and the Muslim families were assisting them. The relations between the two communities were extremely cordial and the village was a happy community, unaffected by what was happening in Lahore and Amritsar . Most of the inhabitants had very few desires and aspirations and that precisely led to their contented lifestyle. The children of the village used to play “Chhattapooâ€, “Pithooâ€, “Kokla Chhapaki†“Gulel and target†as well as hide and seek. Mohammad Rafi’s childhood was not much different from other kids. In addition Mohammad Rafi liked to copy the folk singers in his amateur way.

Mohammad Rafi was always falling in line with most of his villager folks. His education was confined basically to reading and writing in Urdu in Persian script. Cramming up of a little bit of multiplication tables was his other education. In his moments of leisure, he used to carry his family’s and friends’ cattle for grazing in the fields. Intensive cultivation was alien to most of the villagers then and a lot of grassy fields were left untilled for the cattle to graze. As a child Mohammad Rafi always loved to graze cattle. He had heard some local “Mirasis†(Muslims, who’s profession was singing and acting as folk comedians) singing folk songs in semi-classical and other country tunes. He liked this art and his voice was suitable for it. He used to copy the “Mirasis†of his surrounding villages. While grazing cattle he used to sing popular Punjabi folk songs to all and sundry in the village.

Mohammad Rafi was born in 1924 in his ancestral village Kotla Sultan Singh. Radio during those days was in its infancy in Europe and America . India did get some experimental radio in the four metros of Calcutta , Bombay , Madras and New Delhi in 1927. Lahore had a brief stint with amateur radio in 1928. But organized broadcasting came to Punjab in 1936 in the public sector. The newly constructed studio complex opened in Lahore in 1937. Thus up to the age of thirteen, Mohammad Rafi had practically no exposure to radio.

Gramophone (in America phonograph) was already in great demand in the high-end “Bazaars†in the commercial city of Amritsar . Most of the wealthy people had already bought gramophones for their homes. Mohammad Rafi had also heard some music in the “Havelis†(imposing houses of the rich in Punjab ) of Majitha and the Bazaars of Amritsar. Born in Amritsar Indu Bala, was the then leading most “Thumri†singer of India and Kamla Jharia was fast becoming the most prolific “Thumri†and “Ghazal†singer of India. These voices could be heard during those days in the music stores of “Hall Bazaar†in Amritsar . Mohammad Rafi certainly had some exposure to this music. His once in a blue moon visits to the historic “Hall Bazaar†always left behind sweet memories. Bhai Chhaila of Patiala was the most popular Punjabi folk singer of that time and Dina Qawwal of Jalandhar was becoming popular. Both these artists had some impact on Rafi. Agha Faiz of Amritsar was a great gramophone singer. Rafi had heard all these voices. Nevertheless he was happy and blissful in the dusty fields of his village. Every one in the village was his friend and none was his foe. What a life he had?

There was no one in his village to initiate Mohammad Rafi into the intricacies of classical music, which was and still is the mother of all music in India . Unaware of his handicap of not learning classical music, Mohammad Rafi kept singing to himself and to his simple village folks. His father wanted to create better living conditions for his family. One fine morning his father decided to leave for Lahore the capital of Punjab about fifty miles away from their village. Like several other Amritsaris, he was a very good cook and Amritsari cooks were in great demand not only in Lahore , but all over Northern India . His father opened a “Dhaba†(a no frills country style eating house) in Lahore . His food was invariably delicious and the customers both locals and outsiders started thronging to it. Well begun is half done, he sent a massage to his son Mohammad Rafi to come over to Lahore . Mohammad Rafi reached Lahore round about in 1941, at the age of seventeen.

His father got Mohammad Rafi a job at a hair-dresser’s saloon. He used to shave the customers’ beards quite slowly but carefully. In order to keep his customers in good humour, while doing cuttings and shavings he used to keep singing some folk and country songs of Punjab . Rafi’s customers seldom took notice of his slowness, rather they enjoyed his music. One day Jiwan Lal Mattoo, the program executive of music at All India Radio Lahore passed by the hair cutting saloon and he faintly heard young Mohammad Rafi’s enchanting voice and he instantly liked its sweetness, range and tonal quality. He stopped and paused for a while and then entered the shop. He asked Mohammad Rafi if he was interested in becoming a radio singer. On hearing this unsolicited offer, Mohammad Rafi jumped in the air in happiness. In the month of March in 1943, Mohammad Rafi appeared in the audition test at the studios of All India Radio Lahore and to his utter surprise he passed the test. Thus from March 1943, Mohammad Rafi became a radio artist. This happened six months prior to the Nightingale of Punjab Surinder Kaur becoming a radio singer. At about the same time in 1943, after hearing his voice on the radio, a newly emerging film music director Shyam Sunder requested Mohammad Rafi to sing a song for his Punjabi film “Gul Balochâ€. Mohammad Rafi did full justice to this film song and it opened the gates for his future entry into the field of Bombay ’s playback singing.

MOHAMMAD RAFI’S UNEVENTFUL HALF DECADE IN LAHORE

Mohammad Rafi, a genius who rose to be the leading most film singer of the Indian subcontinent, had a modest and uneventful beginning. At the time of his arrival in Punjab ’s capital city of Lahore , from a small village of neighbouring Amritsar district, Mohammad Rafi had absolutely no idea or for that matter no expectation that some day he can be the leading film playback singer of his time. He was a saintly figure since childhood and was contented with his destiny. .

Prior to moving to Lahore , he was married to the daughter of an uncle. Those were the days when child marriages were not uncommon in Northern India . He was less than fifteen when he entered into the wedlock, but he was told by his father-in-law to become self supporting before his wife could join him.

For a couple of years, he was shaving the beards and cutting and dressing the hair of Lahorias. He kept enjoying even this profession thoroughly. He was not earning much money, but whatever he earned was more than enough to keep his soul satisfied and happy. Being a God fearing and honest young man, he had unique patience and bliss to live in whatever condition God desired him to exist. He never aspired to hop from one job to the other for better emoluments. Nature had blessed him with an uncanny unselfishness and utmost satisfaction in life. He never hankered after ill gotten wealth, power and pelf. Light music sprang naturally from his throat and he kept singing for his own pleasure and for the happiness of his customers. But his listeners saw something extraordinary in his sweet, melodious and soul inspiring voice. He was a God fearing person and a regular five times a day “Namaziâ€, but he was not the least bigoted. He could endear himself to any person who came in his contact even for a short-while.

Jiwan Lal Mattoo of the music department of All India Radio Lahore spotted his musical talent in 1943 and after rigorous audition process, he trained Mohammad Rafi to develop into a folk and country singer. The knowledge, practice and appropriate application of classical music is essential for any singer. Jiwan Lal Mattoo imparted the requisite knowledge of the most commonly used classical Raagas in Punjab ’s folk music to Mohammad Rafi. Raga Pahadi was one such raga and Bhairavi was another. Basant and Malhar were some other commonly used ragas in Punjab . In addition to Jiwan Lal Mattoo, Master Inayat Hussain also gave Mohammad Rafi the finer point of folk singing. Mohammad Rafi also got along very well with another music teacher Budh Singh Taan, who also groomed Parkash Kaur and Surinder Kaur. Incidentally both Parkash Kaur and Surinder Kaur were making more money while in Lahore compared to Rafi.

There were several known “Ustad†singers living in Lahore , who in age and years of experience were far more senior to Mohammad Rafi. He never tried to step on their shoes. Budh Singh Taan was also a light singer. Deen Mohammad used to sing as a solo folk singer, in addition to being a leading Qawaal. Agha Faiz of Amritsar was a very sophisticated folk and semi-classical singer. Another product of Amritsar , Shamshad Begum was senior to Mohammad Rafi by six years and born in Kasur child prodigy Noorjehan preceded Mohammad Rafi by four years. Both Umrao-Zia-Begum and Zeenat Begum were also senior to Mohammad Rafi. True to his quality of utter humility, Mohammad Rafi gave a lot of respect to all his seniors in profession. Mohammad Rafi was indeed a great learner. He won’t mind touching the feet of any “Ustadâ€, who was willing to teach him something new in music. That is why, “Ustad†maestros like Dilip Chander Vedi, a leading Dhrupad exponent of Punjab held Mohammad Rafi in high esteem.

Mohammad Rafi had a lot of regards for Bhai Samund Singh ji of Sri Nankana Sahib and a colleague at All India Radio Lahore. Once he said Bhai Samund Singh is so much at home with classical music that he talks in classical music, which we can’t. About Bhai Santa Singh, he used to say “Bhai Santa Singh’s high-pitched calls to the “Guru†can never go unheard. On Bhai Santa Singh’s 1966 visit to Bombay, Mohammad Rafi made it a point to attend each one of his renditions scheduled at various Gurdwaras in the city Similarly when block-buster Punjabi film “Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai†was made in 1969, both Mohammad Rafi and Bhai Samund Singh were its leading singers.

After Mohammad Rafi’s tough nut father-in-law discovered that his son-in-law has become a radio singer, he sent his daughter to join Mohammad Rafi. The couple was very simple, unassuming and very hospitable. Mohammad Rafi had a vast circle of friends and fans. They used to converge to his home to listen to his silken voice. Mohammad Rafi’s wife was never tired of being the hostess. Most Lahorias were fond of drinking, but Rafi had never touched hard liquor in life. His guests also respected his pious restraints and never insisted to drinking in his and his wife’s presence. His music was enough of an intoxicant to his friends.

Several movies in Hindi and Punjabi were made in Lahore during Mohammad Rafi’s stay in that city, but somehow it did not occur to any of the music directors to feature his velvety voice in a song. The only exception was another genius maestro Shyam Sunder, who gave Mohammad Rafi a Punjabi song to record. This film was “Gul Baloch†made in 1943. However this Punjabi film was poorly made and was not going to be a hit and its songs also sank along with the film.

A great music director Pandit Amar Nath liked Mohammad Rafi’s voice, but he had lined up other singers for his songs. Another great music director Master Ghulam Haider liked him too, but he was moving to Bombay . While packing up to leave for Bombay , he whispered in the ears of Mohammad Rafi to join him later on in Bombay . Ghulam Haider left for Bombay in the end of 1943. In his long and wide entourage were included his well known orchestra as well as Lahore ’s famous film singers like Shamshad Begum, Umrao-Zia-Begum and Noorjehan.

On a second call from Master Ghulam Haider, Mohammad Rafi decided to move lock stock and barrel from Lahore to Bombay in 1945. All that he used to earn was mostly spent on entertaining his friends and fans. It should not come as a surprise that Mohammad Rafi had not enough money to buy tickets in economy class for the Frontier Mail to Bombay . On this occasion his long term pampered friends and relatives, including his elder brother, came to his rescue. After an emotional and tearful send off at Lahore Junction, he dis-embarked in Bombay after two days of monotonous train journey. Bombay was the ultimate city of dreams for everyone connected with movies and it proved extremely fruitful for Mohammad Rafi too.

MOHAMMAD RAFI’S METEORIC RISE AFTER INITIAL HICK-UPS IN BOMBAY

Mohammad Rafi was not a part of Master Ghulam Haider’s contingent, when he moved from Lahore to Bombay in the end of 1943. But after receiving several calls from Bombay , Mohammad Rafi finally decided to leave Lahore for Bombay in 1945. While boarding the train in Lahore , he was seen off by hordes of hugging and emotionally charged friends and relatives, but in Bombay there was no such scene. Hardly anyone turned up to receive him. This was a big cultural shock, but Mohammad Rafi was too cool to be agitated by such incidents. He had come to Bombay with a promise, which he had to fulfill at any cost.

Mohammad Rafi sang a couple of film songs in 1945 in Bombay , but due to poor name recognition, these songs did not help him much. However he was paid a lot better. All India Radio gave him rupees twenty five for a whole day of singing in Lahore, but in Bombay he was paid, during those days a whopping sum of rupees three hundred per film song. In order to make both ends meet, he sang privately too in “Mehfilsâ€, among the Punjabi community of Bombay .

Mohammad Rafi’s first big break came late in 1946. Shooting for a Dilip Kumar Noorjehan starrer block-buster film “Jugnu†was started in 1946. This film was directed by Sayyed Showqat Hussain Rizvi and its soul stirring music was composed by Feroze Nizami on the lyrics contributed by Tanvir Naqvi. All at one or the other time had moved from Lahore and other parts of Punjab to Bombay . By this time Noorjehan had already established herself as the leading female film singer. Her competitor was another actress singer Suraiya. Both hailed from Lahore district. Mohammad Rafi was from the neighboring district of Amritsar.

Noorjehan was extremely jovial and witty. She was known to give tough time to her competitors and co-singers. Strongly built, but petite in height, Noorjehan was already in the sound recording studio for the recording of a duet. She was expecting G.M. Durrani to be the other singer. But Feroze Nizami had a better option. Feroze asked Mohammad Rafi to come for rehearsal. When short simply dressed Mohammad Rafi arrived in the studion, Noorjehan erupted into a loud laughter. Being still new in Bombay and pitted opposite a star singer Noorjehan, Mohammad Rafi got nervous. Noorjehan smilingly asked Mohammad Rafi “So little chap you have finally come to Bombay , welcome, welcome, how were things in Lahore ?â€. A nervous Mohammad Rafi remarked “Things are not bad in Lahore , every one over there was missing their baby Noorjehan. On hearing this instant reply from otherwise a quiet man, everyone in the studio erupted into a loud laughter. Most of the members of the orchestra were of course Punjabis. Mohammad Rafi tried his best in rehearsals, but he was under a complex that he was singing opposite a star. When the recording of the duet song “Yahan badla wafa ka be wafayi ke siwa kya hai†was completed, Mohammad Rafi had doubts about his performance. He wanted a retake, but the music director said it is fine.

When the film was released in 1947, this very duet became the best selling song. This gave the necessary break to Mohammad Rafi and from then on he never looked back and went from strength to strength. Mohammad Rafi’s price tag per song recording jumped to rupees five hundred, the same as Noorjehan’s.

After the release of film “Jugnuâ€, Mohammad Rafi became a much sought after playback singer. Ghulam Haider was composing music for another block-buster film “Shaheedâ€. Surinder Kaur was its leading female singer, but one song sung by Mohammad Rafi “Watan ki raah main watan ken au jawan shaheed ho†became so popular that Mohammad Rafi became a household name. This song was recorded in 1948 and released during the same year.

Born on April 11, 1904 the reigning male singing star K.L. Saigal died on January 18, 1947 at the age of forty two. Like a “Banyan†tree K.L. Saigal was larger than life, no other singer could grow to potential under his shadow. Being trained in Calcutta , K.L. Saigal’s style of singing had the tinge of semi-classical musician with a Bengali finesse. But Mohammad Rafi’s style was a lot more flexible and suitable for every actor. G.M. Durrani was another Punjabi singer, who in years was senior to Mohammad Rafi. The top slot left open by K.L. Saigal’s demise took some time to be filled.

A lot of music directors came forward to groom and polish the singing skills of Mohammad Rafi.

|

|

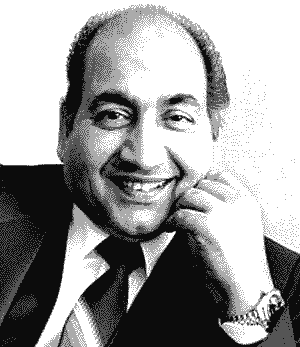

Pundit Husnalal Playing his favorite instrument violin |

Among the foremost were Shyam Sunder (an import from Lahore ), Pandit Husnalal Bhagatram (another import from lahore ), famous drummer Ustad Allah Rakha (originally of Gurdaspur district) Naushad Ali from U.P. and Sajjad Hussain. In fact once Sajjad Hussain asked Mohammad Rafi to sing “Heer Waris Shah†for him. Mohammad Rafi sang it with typical Amritsari slang. Sajjad composed its tune in his own inimitable style. With a lot of effort Mohammad Rafi mastered the new tune, but the end product was great.

|

|

Pundit Husnalal rhearsing a tune with Mohammad rafi |

Pandit Husnalal offered to train Mohammad Rafi into a top notch film singer. When Husnalal Bhagatram started their career as a duo of music directors in 1944, they depended thoroughly on the seasoned voice of Zeenat Begum a discovery of their elder brother Pandit Amar Nath. But during the late forties much shriller female voices started dominating the film scene. Amongst men Mohammad Rafi was senior in years to Mukesh and Manna Dey. Talat Mahmood had started earier than Mohammad Rafi in 1941 in Calcutta . But in Bombay Talat Mahmood came a couple of years later than Mohammad Rafi.

When the opportunities came Mohammad Rafi pounced on them. Then came August 15, 1947 . What Mohamad Rafi observed will be covered in the next issue?.

MOHAMMAD RAFI’S DOMINATION IN FILM SINGING AND THE PARTITION OF INDIA

By the middle of 1947, Mohamad Rafi had become a household name in Hindi speaking North India . His flexible, sweet and velvety voice suited most young actors including the brilliant rising star Dilip Kumar. Most of the finest music directors, spearheaded by the duo of Pandit Husnalal Bhagatram, were showing interest in grooming his raw talent further into the art of film playback singing.

In his ancestral province of Punjab , the communal divide was on the rise. In March of 1947 some five hundred Sikhs and some Hindus were gruesomely murdered in Rawalpindi area, which was not too far away from his ancestral home in Amritsar district and his recent professional home Lahore . Even during those days such gruesome news was difficult to hide. Those ugly news slowly trickled into his new home city of Bombay . Mohammad Rafi had seen excellent communal relations in his ancestral village in rural Amritsar , this barbaric news came as an unbelievable shock to this God fearing and sensitive young-man.

By August the matters had taken a turn for the worst in his home province. Entire Lahore division had exploded into communal frenzy of the worst kind. There were massacres of Sikhs and Hindus in Gujjranwala, Sheikhupura, Nankana Sahib, Sialkot , Lahore and Kasur. Soon afterwards, the Sikh frenzy erupted in Amritsar , Gurdaspur and Ferozepore. There was complete anarchy on both sides of the Radcliffe line and all districts of Punjab were engulfed in bitter communal riots.

|

|

Sardul Kwatra - Amarjit Chandan's collection- Date unknown |

Renowned film producer Roop K. Shori and music director Vinod had arrived in Indian Punjab bereft of all their belongings from Lahore soon after the outbreak of communal riots. On arrival in Bombay , they were narrating many heart rending stories of cold blooded tyranny. The Shoris had not only lost their film studio in Lahore , they lost all their wealth and property. Vinod came to Amritsar in a penniless condition. Vinod had become a good friend of Mohammad Rafi. In a futile attempt to see the return of better days in Lahore , another music director Sardul Singh Kwatra had spent some days after partition in Lahore . He narrated to Mohamad Rafi some first hand accounts of uncontrolled massacres in Lahore and its vicinity. Sardul was very fair-minded in his description of the communal riots. He had seen tyranny on both sides of the communal divide. He narrated “Things were extremely bad in Gujjranwala, Sheikupura, Sialkot and Lahore , but the retribution seen in Amritsar was a lot more horrifyingâ€. Sardul Kwatra, knew Mohammad Rafi since his days in Lahore . Later on Sardul became a collection agent and business representative of Mohammad Rafi. Mohammad Rafi had all along been a God fearing and righteous gentleman. He always bowed before the will of the most benevolent “Khudaâ€. At every available opportunity, he lent his sweet silken voice to every song composed for fostering communal harmony and brotherhood amongst the Hindus, Sikhs and the Muslims in all parts of India .

Pandit Husnalal Bhagatram had composed several tunes for the lyrics penned to depict the horrors of the partition and the resultant bloodbath. One such song was “Is dil ke tukde hazaaar huye, koi yahan gira koi wahan gira, behte huye aansoo ruk na sake koi yahan gira koi wahan giraâ€. The literal meaning of this is that a heart was broken into thousands of pieces and the pieces were scattered all over the place, some here and some there. A truly hurt Mohammad Rafi gave his emotion filled voice to this song. This song became an instant hit on both sides of the border. The sad assassination of Mahatma Gandhi was also caused as a result of the bitterness generated between the Hindus and Muslims. Pandit Husnalal Bhagatram composed an emotional tune for a song describing the life story of Mahatma Gandhi. The wording was “Suno suno aye duniya walo baapu ki yeh amar kahaniâ€. This song also became very popular in Northern India .

From early 1948 Pandit Husnalal decided to groom two young voices for the film industry. Mohammad Rafi was his choice among the male singers and Lahore born actress singer Suraiya was his choice as a female singer. Pandit Husnalal used to call Mohammad Rafi, sometimes as early as at 4am , to his home along with his Tanpura. He used to give lessons in different “Raagas†and asked him to rehearse those “Raagas†in “Khayal†format. This basic training in classical music continued for several years and it went on to make Mohammad Rafi a high-class versatile singer. It was difficult for a young beautiful lady like Suraiya to come to a music director’s place at odd hours to learn the basics of music. So Suraiya unfortunately did not learn classical music, but she was very persevering on light music and she always rehearsed her assignments in the studios to perfection. .

By late 1948 Lata Mangeshkar came in contact with Pandit Husnalal. She was a very versatile singer. Her grasp and learning ability of classical music was very quick. Pandit Husnalal discovered that training of Lata Mangeshkar could be a lot more rewarding. So he slowly started preferring Lata Mangeshkar over a more emotional and sorrow filled voice of Suraiya. As far as the male artists were concerned, Mohammad Rafi has always been Pandit Huisnalal’s first preference. A lot of times, on the specific recommendations of the top lyricists of the day, Pandit Husnalal Bhagatram gave the best “Ghazals†to Talat Mahmood to render in his unmatched linguistic sophistication. Most of the “Ghazals†sung by Talat Mahmood also became very popular. Mohammad Rafi never entertained any jealousies with any singer whatsoever. He invariably admired Mukesh, Manna Dey, Talat Mahmood and Hemant Kumar for the uniqueness of their voices.

|

|

Music Director Vinod |

Mother language is a great bond that binds human-beings. This was more true In the case of Mohammad Rafi. His first ever film song was composed by a Punjabi music director Shyam Sunder and his first nationwide film hit was composed by another Punjabi music director Feroze Nizami. Since 1948, in Bombay , his voice was initially used by Punjabi music directors such as Master Ghulam Haider, Pandit Husnalal Bhagatram, Vinod, Shyam Sunder, Allah Rakha Quraishi, Hans Raj Behl, S. Mohinder and Sardul Kwatra. After his songs became hits regularly, most other music directors including Naushad also started patronizing him.

Master Ghulam Haider’s brilliant tune composed for film “Shaheedâ€, rendered by Mohammad Rafi for the patriotic song “Watan ki raah mein watan ke naujwan shaheed hoâ€, which became the signature tune for the movie, became overnight a nationwide hit. Even now on India ’s national days such as the independence- day and the republic day, this particular song is proudly played by All India Radio.

Maverick music director Shyam Sunder’s tunes rendered by Mohammad Rafi for film “Bazaar†(1949) including a duet with Lata Mangeshkar entitled “Apni nazar se door voh, unki nazar se door hum, tum hi batao kya Karen, majboor tum majboor hum†caught the imagination of entire Hindi knowing India. Allah Rakha Qureishi used Mohammad Rafi’s and Surinder Kaurs’s voices in film “Sabak†with a fairly good response from the public. Vinod’s music for his 1949 film “Ek thi ladki†was a super-hit. Most of its songs were rendered by Lata Mangeshkar, but the Lata Rafi duet “Khamosh nigahein†reserved a proud place on the popularity charts. Hans Raj Behl’s song “Jugg wala mela yaaro thohri der daa, hassdiyan raat langhe pata nahin saver da†rendered by Mohammad Rafi for his Punjabi block-buster film “Lachhi†(1949) had appeal which transcended the boundaries of Punjab . On popular demand the same tune was used later on for a Hindi song too. Mohammad Rafi’s Punjabi duet with Lata Mangeshkar entitled “Kaali kanghi naal kale waal payi vaahuniyan, aa mil dhol janiyan†for film “Lachhi†also created waves among the lovers of Punjabi music in Northern India . Sardul Singh Kwatra composed soul inspiring music for a humorous Punjabi film “Postiâ€. Its music was recorded in 1949, but the film was released in 1950. One of its masterpiece duet songs rendered by Mohammad Rafi with debutant playback singer Asha Bhonsle entitled “Too peengh te mein parchhawan, tere naal hulare khawan, laalay dostiâ€, achieved a lot of popularity in Punjabi knowing India.

Mohammad Rafi’s utmost devotion to his profession and hard work under the music direction of Pandit Husnalal Bhagatram paid great dividends and he became India ’s leading duet singer in the company of Lata Mangeshkar. Some of his pre-1950 duets with Lata Mangeshkar are acclaimed as some of the finest in the history of film singing. I shall mention two of these. One was “Khushi kaa zamaaana gaya rone se ab kaam hai, pyaar jiskaa naam tha judayi uska naam hai†recorded for film “Chhoti Bhabiâ€, based on an old Punjabi folk tune, was the personal favourite of music director Sardul Kwatra. Sardul even used this tune for one of his later songs in Punjabi. Another Husnalal Bhagatram masterpiece duet was “Paas aake huye hum door, yehi tha qismat kaa dastoor†recorded for film “Meena Bazaarâ€, it became Mohammad Rafi’s favourite song. This film did not do too well in the cinema halls, but its music became the proud possession of the most discriminating collectors of music including Allahdad Khan of Peshawar .

After 1950 most of the great music directors of India considered Mohammad Rafi a force in film music. When Naushad composed his masterly tunes for films like “Dulari†(1949) and “Deedar†(1951), Mohammad Rafi became the star that no one could afford to ignore. Film “Deedar†song entitled “Huye hum jin ke liye barbad†became an all time hit. Later on his high pitched numbers sung for films “Amar†and “Baiju Bawra†put him up at a very high pedestal. Mohammad Rafi was honest to the core, never greedy and success did not make him arrogant.

When, after initial setbacks, O.P. Nayyar, as a music director, attained a place of prominence in the film world in 1953, Mohammad Rafi became his first choice as a male singer and the duets sung by Mohammad Rafi with Asha Bhansale as well as with Shamshad Begum became extraordinarily popular. Mohammad Rafi never charged a penny from music director Sardul Singh Kwatra for any song rendered on Sardul’s music. He did the same favour for several years to most of the music directors, who migrated from what is now Pakistan . He also helped a fellow Amritsari singer Mohinder Kapoor in becoming a playback singer.

In his religious life Mohammad Rafi was always a true five-time “Namazi†and a strict “Momenâ€. But in his professional life he has been a liberal secularist. He visited the “Gurdwaras†like a Sikh used to during his younger days. Even while living in Bombay he visited the “Gurdwaras†on special festive occasions and during the visits to Bombay of iconic Sikh “Raagis†like Bhai Santa Singh ji and Bhai Samund Singh ji. He missed no opportunity to visit Bombay ’s famous annual Baisakhi Mela. Throughout his singing career Mohammad Rafi sang several memorable “Naatsâ€, but he lent his voice equally well to extremely soulful “Bhajans†(on the tunes composed by icons like Naushad) and some melodious “Shabads†(on the tunes mostly composed by music director S. Mohinder).

What Mohammad Rafi did and achieved after 1952-53 has been recorded by several other historians and writers on film music and I shall not dwell on that period. My desire was to unfold his impressionist younger years and the years of his grim struggle to reach the pinnacle of success. My head will always bow in admiration before Mohammad Rafi the Great. May his soul, rest in piece for ever in his heavenly abode. Such pious individuals are rarely born on this earth.

harjapaujla@gmail.com

Read more

Punjab must be genuinely proud of its great son Mohammad Rafi, who was born in a non-descript hamlet in a remote rural area of Amritsar district. Starting from a humble and modest beginning, he rose to become the most prolific film playback singer of the movie industry, not only in

Punjab must be genuinely proud of its great son Mohammad Rafi, who was born in a non-descript hamlet in a remote rural area of Amritsar district. Starting from a humble and modest beginning, he rose to become the most prolific film playback singer of the movie industry, not only in

[1]-200.gif)

Sometimes I feel that there are several important aspects of the history of Punjab, which have gone unrecorded. Although Punjabi pop music is currently dominating the musical scene of India, yet no one has taken pains to discover the pioneering times of its mother, the folk and light Punjabi music. I have hardly seen any material on the history of Punjabi cinema. This article is an attempt to record whatever I know about the history of Punjabi film music.

Sometimes I feel that there are several important aspects of the history of Punjab, which have gone unrecorded. Although Punjabi pop music is currently dominating the musical scene of India, yet no one has taken pains to discover the pioneering times of its mother, the folk and light Punjabi music. I have hardly seen any material on the history of Punjabi cinema. This article is an attempt to record whatever I know about the history of Punjabi film music. History of Punjabi films is almost as old as that of Hindi cinema. The first talkie in Hindi Alam Ara was made in 1931 and the first Punjabi film was made in 1934, its print is unfortunately lost to our callous indifference towards our heritage. It is never too late to start preservation, I think it is time we should establish an archive of our old films and their music.

History of Punjabi films is almost as old as that of Hindi cinema. The first talkie in Hindi Alam Ara was made in 1931 and the first Punjabi film was made in 1934, its print is unfortunately lost to our callous indifference towards our heritage. It is never too late to start preservation, I think it is time we should establish an archive of our old films and their music. Based on my research, I shall divide Punjabi music directors into three distinct generations. The first being the generation of pioneering music directors, who had no role models to follow? The second generation being that of the trendsetters and the third is the post 1980 period of pop music and innovations in folk. I shall not attempt to write about the contemporary music directors, who are currently composing the Punjabi music and making big bucks. I think it will be more appropriate to write about the strugglers of 1934 to 1979 period, who’s memories are already fading and very soon the people will start forgetting them.

Based on my research, I shall divide Punjabi music directors into three distinct generations. The first being the generation of pioneering music directors, who had no role models to follow? The second generation being that of the trendsetters and the third is the post 1980 period of pop music and innovations in folk. I shall not attempt to write about the contemporary music directors, who are currently composing the Punjabi music and making big bucks. I think it will be more appropriate to write about the strugglers of 1934 to 1979 period, who’s memories are already fading and very soon the people will start forgetting them. The second generation consists of among others Khurshid Anwar, Feroze Nizami, Rashid Atre, Master Inayat Hussain, Shyam Sunder, Pandit Husna Lal, Bhagat Ram, Hans Raj Behl, Vinod, Alla Rakha Qureishi, Shiv Dayal Batish, Madan Mohan, Sardul Kwatra, S. Mohinder, Roshan, Ravi, Khayyam, K. Panna Lal, Pandit Amarnath Second, O.P. Nayyar and Usha Khanna. Some of them did not compose music for Punjabi films, but by origin all of them were Punjabis.

The second generation consists of among others Khurshid Anwar, Feroze Nizami, Rashid Atre, Master Inayat Hussain, Shyam Sunder, Pandit Husna Lal, Bhagat Ram, Hans Raj Behl, Vinod, Alla Rakha Qureishi, Shiv Dayal Batish, Madan Mohan, Sardul Kwatra, S. Mohinder, Roshan, Ravi, Khayyam, K. Panna Lal, Pandit Amarnath Second, O.P. Nayyar and Usha Khanna. Some of them did not compose music for Punjabi films, but by origin all of them were Punjabis. Out of all these, the ones I know intimately are S. Mohinder and Late Sardul Singh Kwatra. This article is about the life and works of Sardul Kwatra (1928 – 2005). Sardul Singh Kwatra was born and brought up in Punjab’s capital Lahore. Since childhood Sardul was fond of music. Lahore was a place where Punjab’s finest maestros attained name and fame. Sardul while studying in school got the initial training in classical music from Sardar Avtar Singh. Sardar Avtar Singh possessed good knowledge of most of the Ragas mentioned in Sri Guru Granth Sahib as well as those Ragas, upon which the folk tunes of Punjab are based. Among the male voices Sardul was a great admirer of Agha Faiz of Amritsar and among the females he was especially fond of the silken voice of Zeenat Begum.

Out of all these, the ones I know intimately are S. Mohinder and Late Sardul Singh Kwatra. This article is about the life and works of Sardul Kwatra (1928 – 2005). Sardul Singh Kwatra was born and brought up in Punjab’s capital Lahore. Since childhood Sardul was fond of music. Lahore was a place where Punjab’s finest maestros attained name and fame. Sardul while studying in school got the initial training in classical music from Sardar Avtar Singh. Sardar Avtar Singh possessed good knowledge of most of the Ragas mentioned in Sri Guru Granth Sahib as well as those Ragas, upon which the folk tunes of Punjab are based. Among the male voices Sardul was a great admirer of Agha Faiz of Amritsar and among the females he was especially fond of the silken voice of Zeenat Begum. Sardul thought that Zeenat’s voice was culturally very well marinated into music. He was also a great admirer of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and his brother Barqat Ali Khan. Since his childhood Sardul Kwatra had a fairly good knowledge of the basic tunes of Central Punjab’s folk songs like “Heerâ€, “Mirzaâ€, “Tappeâ€, “Bolianâ€, “Jugniâ€, “Dholaâ€, “Mahiyaâ€, “Multani Kafi†and “Saiful Malookâ€. Such knowledge came in handy when later on Sardul became a film music director.

Sardul thought that Zeenat’s voice was culturally very well marinated into music. He was also a great admirer of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and his brother Barqat Ali Khan. Since his childhood Sardul Kwatra had a fairly good knowledge of the basic tunes of Central Punjab’s folk songs like “Heerâ€, “Mirzaâ€, “Tappeâ€, “Bolianâ€, “Jugniâ€, “Dholaâ€, “Mahiyaâ€, “Multani Kafi†and “Saiful Malookâ€. Such knowledge came in handy when later on Sardul became a film music director. I had my first exposure to his film music, when I saw the first “Kwatra Production†a Punjabi film “Posti†in 1950 in New Delhi. Being a child I could not understand the story, but I certainly enjoyed the music and still remember its songs and tunes. In person, I saw him in 1957 in Amritsar, when he came there to accompany Mohammad Rafi in a mixed Hindi Punjabi film song concert. He was playing piano accordion and serving as the master of ceremony.

I had my first exposure to his film music, when I saw the first “Kwatra Production†a Punjabi film “Posti†in 1950 in New Delhi. Being a child I could not understand the story, but I certainly enjoyed the music and still remember its songs and tunes. In person, I saw him in 1957 in Amritsar, when he came there to accompany Mohammad Rafi in a mixed Hindi Punjabi film song concert. He was playing piano accordion and serving as the master of ceremony. The second opportunity came my way when I met Sardul Kwatra in the Madhya Marg shopping center in Sector 7, Chandigarh. It was a surprise meeting. I saw someone resembling Sardul Kwatra that I had seen in 1957. On asking he said that he indeed is Sardul Kwatra and has shifted from Bombay to Chandigarh. He said he is rediscovering his roots and wants to open a film institute in this city, where he will impart training in acting, direction, singing, dancing and tune making. I was thrilled to hear all that. From that chance meeting on we used to meet often in his “Chandigarh Film Institute†located in a sprawling Sector 5 house only a stone’s throw away from Sukhna Lake. There were chatting sessions in this building, the adjoining lake and at my house in Sector 11 that gave me a peep into his achievements and failures.

The second opportunity came my way when I met Sardul Kwatra in the Madhya Marg shopping center in Sector 7, Chandigarh. It was a surprise meeting. I saw someone resembling Sardul Kwatra that I had seen in 1957. On asking he said that he indeed is Sardul Kwatra and has shifted from Bombay to Chandigarh. He said he is rediscovering his roots and wants to open a film institute in this city, where he will impart training in acting, direction, singing, dancing and tune making. I was thrilled to hear all that. From that chance meeting on we used to meet often in his “Chandigarh Film Institute†located in a sprawling Sector 5 house only a stone’s throw away from Sukhna Lake. There were chatting sessions in this building, the adjoining lake and at my house in Sector 11 that gave me a peep into his achievements and failures. I was fascinated by Sardul Kwatra’s brilliance as a music director of Punjabi films. His tunes reflected the real folk music of Punjab, the music of Lahore and Central Punjab of pre-partition era. His musical score for some Hindi films is also at par with that composed by some of the stalwarts of Hindi film music. Sardul disclosed that he has always been a highly romantic person and his best tunes were composed during various episodes of romancing.

I was fascinated by Sardul Kwatra’s brilliance as a music director of Punjabi films. His tunes reflected the real folk music of Punjab, the music of Lahore and Central Punjab of pre-partition era. His musical score for some Hindi films is also at par with that composed by some of the stalwarts of Hindi film music. Sardul disclosed that he has always been a highly romantic person and his best tunes were composed during various episodes of romancing. The first production of the Kwatra family was film “Postiâ€. The idea took shape while the family was still in Lahore, but the partition of Punjab left the family high and dry. After a short duration in Amritsar, the family moved to Bombay virtually penniless. Most of the cast of the film had also arrived in Bombay. Majnu, a Christian stage and film artist of Lahore performed the leading male’s role as Posti. Bhag Singh performed his father’s role. The heroine’s father was a very popular actor Ramesh Thakur. The lady for the role of the heroine was still being searched. Sardul Kwatra took it upon himself to choose a heroine.

The first production of the Kwatra family was film “Postiâ€. The idea took shape while the family was still in Lahore, but the partition of Punjab left the family high and dry. After a short duration in Amritsar, the family moved to Bombay virtually penniless. Most of the cast of the film had also arrived in Bombay. Majnu, a Christian stage and film artist of Lahore performed the leading male’s role as Posti. Bhag Singh performed his father’s role. The heroine’s father was a very popular actor Ramesh Thakur. The lady for the role of the heroine was still being searched. Sardul Kwatra took it upon himself to choose a heroine. Sardul Kwatra said that he was a great admirer of the femininity and beauty of “Shyama†and Shyama was a natural dancer, who will instantly start dancing to the tune composed. Sardul never touched Shyama, but being a silent admirer, he created some of the most everlasting Punjabi tunes.

Sardul Kwatra said that he was a great admirer of the femininity and beauty of “Shyama†and Shyama was a natural dancer, who will instantly start dancing to the tune composed. Sardul never touched Shyama, but being a silent admirer, he created some of the most everlasting Punjabi tunes. The Kwatra family shortly there after made a Hindi film “Mirza Sahiban†also in 1953. The hero was Shammi Kapoor, but the heroine once again was Shyama. This film did not do too much business, but it launched Sardul Kwatra as a music director for the mainstream Hindi cinema. Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammad Rafi sang most of its songs. The music became more popular than the movie. One Punjabi song in Rafi’s voice “Nahin Rees Punjab Di, Kehndi e Lehar Charab Di†became very popular all over Punjab.

The Kwatra family shortly there after made a Hindi film “Mirza Sahiban†also in 1953. The hero was Shammi Kapoor, but the heroine once again was Shyama. This film did not do too much business, but it launched Sardul Kwatra as a music director for the mainstream Hindi cinema. Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammad Rafi sang most of its songs. The music became more popular than the movie. One Punjabi song in Rafi’s voice “Nahin Rees Punjab Di, Kehndi e Lehar Charab Di†became very popular all over Punjab. Sardul Kwatra scored the music for a Hindi film “Pilpli Sahibâ€. Its songs are great pieces of art. Sardul did not hide his admiration for actress singer Suraiya. He always longed to compose tunes for her. Suraiya was a real star. She was rich and classy. She used to travel in a shoffer driven long black Cadillac Sedan. It was a treat to watch this VIP. In 1957, Suraiya accepted Sardul Kwatra’s request.

Sardul Kwatra scored the music for a Hindi film “Pilpli Sahibâ€. Its songs are great pieces of art. Sardul did not hide his admiration for actress singer Suraiya. He always longed to compose tunes for her. Suraiya was a real star. She was rich and classy. She used to travel in a shoffer driven long black Cadillac Sedan. It was a treat to watch this VIP. In 1957, Suraiya accepted Sardul Kwatra’s request.